TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction – 2

The Liturgy’s Beginnings and Rationale – 3

High Church – Low Church – 6

Different Liturgies in Lutheran Service Book –7

A Three-Part Service – 8

Announcements – 9

Opening Hymn – 9

Invocation – 10

Facing the Altar or the Congregation – 10

Making the Sign of the Cross – 10

Amen – 11

Confession of Sins and Absolution – 11

Introit/Psalm – 13

Kyrie – 15

Hymn of Praise – 16

Salutation and Collect of the Day – 19

Appointed Scripture Lessons – .20

Creed – 22

Sermon – 23

Offering – 23

Prayer of the Church – 24

Service of the Sacrament – 26

Preface – 26

Sanctus – 28

The Communion Prayers – 30

The Words of Our Lord/Words of Institution – 31

Pax Domini – .33

Agnus Dei – 33

The Distribution – 34

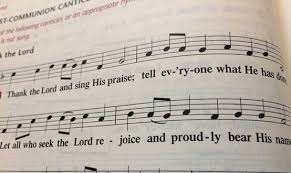

Nunc Dimittis/Thank the Lord – 35

Post-Communion Prayer – 36

Thanksgiving – 37

Salutation and Benedicamus – 37

Benediction – 37

Parting Words – 38

-1-

Introduction

There are many different styles of worship today. In a typical Sunday service, in my denomination (The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod) we use a format called “liturgical.” We are not mandated to use it, we just do. It is a style that has been used since the days of Jesus. It is a style that has shaped the spiritual lives of countless Christians. It is the style used by people like Augustine, Gregory the Great, Martin Luther, and so many others. It has been tweaked by Christians from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Europe, North and South America, Australia, and the islands of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It is still being tweaked. It is truly a global style, belonging to no particular nation or culture. It is a style that brings to us the good gifts of God in Word and Sacrament. It is a style that keeps our hearts and minds focused on Jesus.

Lutherans are by no means the only Christians that use a liturgical format in their worship services. Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Presbyterians, Methodists, Anglicans, and so many others, do as well. We each adjust the tradition to reflect our understanding of worship and theology, but we all draw our liturgical water from the same well.

With all that being said, it is also a style that many in modern America do not understand. That includes people in churches that use some form of the historic liturgy. This was pointed out to me by our “worship discussion group,” that asked me to write a series of articles for our newsletter on the topic of our worship style. So, to help the members of my local church (Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, Newark, DE) to better understand our liturgical worship style and thereby derive even more benefit from it, I wrote a series of articles for our newsletter. The series was titled “Worship with the Saints.” Now that I have finished the series, I’ve decided to post it on our blog. Certain modifications have been made to make it read smoothly or to clarify things.

It is worth noting that this is not a comprehensive look at the liturgy. Technical terms are kept to only those used in our hymnal, and those are explained. It is also not a look at all the possible liturgical services (Matins, Vespers, etc.). It is only a look at the primary Sunday morning worship services found in the Lutheran Service Book and is written with the informed Christian adult in mind, but one with little advanced liturgical training.

It is worth noting that this is not a comprehensive look at the liturgy. Technical terms are kept to only those used in our hymnal, and those are explained. It is also not a look at all the possible liturgical services (Matins, Vespers, etc.). It is only a look at the primary Sunday morning worship services found in the Lutheran Service Book and is written with the informed Christian adult in mind, but one with little advanced liturgical training.

-2-

I need to make a disclaimer. The liturgical style of worship is not commanded by God. As such, there are Missouri Synod Lutheran churches that do not use the liturgical format in our hymnal, but whose doctrine is completely orthodox. Lutheran unity is based on doctrine, not worship style. Lutheran doctrine on worship style is expressed in the Epitome, Formula of Concord, Article X, Church Usages, Thesis 2. “We believe, teach and confess that the community of God in every locality and every age has the authority to change such ceremonies and practices, according to circumstances, as it may be most profitable and edifying to the community of God.” In the same Article X we read, “churches will not condemn each other because of a difference in ceremonies, when in Christian liberty one uses fewer or more of them, as long as they are otherwise agreed in doctrine and all its articles … according to the well-known axiom, ‘Disagreement in fasting should not destroy agreement in faith.’” So, to all who may read this, please remember that it is about how we worship at Our Redeemer, and how many of our sister congregations worship, but we pass no harsh judgment on other churches that may have more or fewer ceremonies.

I need to make a disclaimer. The liturgical style of worship is not commanded by God. As such, there are Missouri Synod Lutheran churches that do not use the liturgical format in our hymnal, but whose doctrine is completely orthodox. Lutheran unity is based on doctrine, not worship style. Lutheran doctrine on worship style is expressed in the Epitome, Formula of Concord, Article X, Church Usages, Thesis 2. “We believe, teach and confess that the community of God in every locality and every age has the authority to change such ceremonies and practices, according to circumstances, as it may be most profitable and edifying to the community of God.” In the same Article X we read, “churches will not condemn each other because of a difference in ceremonies, when in Christian liberty one uses fewer or more of them, as long as they are otherwise agreed in doctrine and all its articles … according to the well-known axiom, ‘Disagreement in fasting should not destroy agreement in faith.’” So, to all who may read this, please remember that it is about how we worship at Our Redeemer, and how many of our sister congregations worship, but we pass no harsh judgment on other churches that may have more or fewer ceremonies.

May the Lord we worship use this little work to enrich your Sunday morning worship.

The Liturgy’s Beginnings and Rationale

The style of worship we use at Our Redeemer is often called “liturgical” because we follow the historic “liturgy” handed down in the western tradition. It is not, therefore, uniquely Lutheran. Many Christian Confessions also use the western liturgical tradition to shape their Sunday morning worship. Of course, each of these larger confessions brings their own distinctive theology to the worship tradition, so these various denominations are not carbon copies of each other on Sunday morning. For example, the new Presbyterian hymnal has baptisms at the end of the service, reflecting their theology of baptism. Lutherans tend to do baptisms early in the service reflecting, not only the historical position of this Sacrament, but also our theology concerning baptism.

To understand the liturgy we need to understand the message and the history of Christian worship. It is a message and a history that is centered on the central event of all time: the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the reason our Lord had to die and rise: our sinfulness. In-other-words, the liturgy proclaims Law and Gospel, Sin and Grace.

-3-

There is some debate on how we are to understand the word “liturgy.” It is a combination of two Latin words, “leit” meaning people and “ergon” meaning work. The Greek word, from which the Latin is taken, has the same two meanings.

As I grew up, the dominant idea was that “liturgy” means “the work of the people.” We were taught that it is not intended to be easy. Nor is it intended to be a reflection of popular culture. It introduces us to the historic culture, language and message of the Church. It helps form us as Christians. As no true Christian life is possible without our own involvement, the liturgy demands the worshipers to participate through sung and spoken responses, by kneeling and standing (Philippians 2:12).

In recent decades, scholarly opinion has been quickly shifting towards the idea that “liturgy” means “[God’s] work for the people.” In this view God comes to his people, working through Word and Sacrament, to form us into his “peculiar” people (1 Peter 2:9). It is, therefore, not a reflection of the current culture’s trends, but a reflection of how God has chosen to come to his people and shape them throughout the ages and across every continent. (It is this view that is reflected in Lutheran Service Book’s use of the word “Divine” in naming our main Sunday morning services.)

Both ideas have merit, in my opinion. We may favor one while admitting the value of the other. The simple fact is that, in the liturgy, God does come and serve us through Word and Sacrament and we do respond in faith towards him and fervent love one another (to quote Luther’s post-communion collect).

Both ideas have merit, in my opinion. We may favor one while admitting the value of the other. The simple fact is that, in the liturgy, God does come and serve us through Word and Sacrament and we do respond in faith towards him and fervent love one another (to quote Luther’s post-communion collect).

It is also worth knowing that the popularity of the word “liturgy” is relatively recent in terms of the overall history of the Church. It began to catch on in English-speaking countries in the 1800s. Prior to that, what we call in the Lutheran Service Book “the Divine Service” was called the “mass.” That is the term used in the Lutheran confessional writings; another word used is “ceremonies.”

-4-

The Church inherited its primitive liturgy from the Jewish Synagogue. They immediately gave it a New Testament character by adding the Lord’s Supper, which proclaimed Jesus’ death and resurrection (Acts 2:42; 1 Corinthians 11:26). While they adopted the Synagogue’s practice of reading from the Old Testament during the service, the Church soon added readings from the letters written by the Apostles and the Gospels (Colossians 4:16; Revelation 22:18-19). Before the Apostle John died a creed very similar to the Apostles’ Creed was already in use (more on this under the heading “Creed”). So the first-century Christian worship service was already a liturgy of word and sacrament.

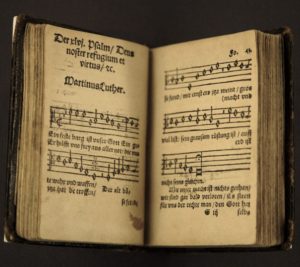

Singing was also important in the early worship service (Mark 14:26; Ephesians 5:19; Colossians 3:16). Singing is a natural thing to do when you celebrate, and Christian worship is about celebrating our redemption. Singing also makes the biblical message more memorable. We literally sing the word of God into our hearts (to loosely quote Luther).

Singing was also important in the early worship service (Mark 14:26; Ephesians 5:19; Colossians 3:16). Singing is a natural thing to do when you celebrate, and Christian worship is about celebrating our redemption. Singing also makes the biblical message more memorable. We literally sing the word of God into our hearts (to loosely quote Luther).

The changeable parts in the service, like the Gradual and Bible readings, are called “Propers” and reflect the theme of the day or season (the various Propers are considered below). The fixed features of the service, called “Ordinaries,” reflect the general theme of redemption (more on the various Ordinaries below). Often the Propers and Ordinaries are set to music.

The hymns used during the worship service may reflect the themes of the day (found also in the assigned scripture lessons, Collect (Prayer) of the Day, etc.) or season (like Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, etc.), as well as where we are in the service (Invocation, Confession and Absolution, etc.). They may also reflect something special in the church’s history, like an anniversary or confirmation. Finally, they may reflect some aspect of the regular secular calendar like Independence Day or Mother’s Day. (Okay, sometimes a hymn is picked because it is a favorite and hasn’t been sung in a while.) It is always worthwhile to reflect on why the hymns being sung on any given Sunday have been chosen.

-5-

High Church – Low Church

Before moving on to more specific parts of the service, we shall consider a couple of other general things, including the difference between “high” church and “low” church worship practices.

Often when people speak of “high” church, they are thinking of vestments, paraments, bells, organ music (especially pipe organ), incense, and the like. In other words, they seem more ornate and express earlier cultures. It might be surprising, but in the narrow and “proper” use of the term, “high church” refers to none of these things. A “high church” worship service includes chanting. A “low church” worship service is spoken, hymns being the only exception.

Often when people speak of “high” church, they are thinking of vestments, paraments, bells, organ music (especially pipe organ), incense, and the like. In other words, they seem more ornate and express earlier cultures. It might be surprising, but in the narrow and “proper” use of the term, “high church” refers to none of these things. A “high church” worship service includes chanting. A “low church” worship service is spoken, hymns being the only exception.

While this is the technical difference between “high church” and “low church,” the everyday use of the terms (I feel) is that “high church” worship services use the historic liturgy and “low church” worship services do not. The feeling is that “high church” services are more ornate and “low church” services are plainer. I have no idea how this thinking translates to people who attend “contemporary” worship services with a healthy dose of pop music, banners, video screens, multiple choirs, skits, plays, and so forth. They seem rather ornate to me even though they are not using historic words. Because they don’t chant, they are technically “low church,” but boy can they be fancy. If, in the popular mind, “high church” means fancy and “low church” means plain, then they are certainly “high church.”

Because we include chanting in our Sunday morning worship services at Our Redeemer they are, technically, “high church.” At our mid-week Bible studies, we begin our time together using Responsive Prayer (Suffrages). Because there is no chanting they are “low church.” That is so even though we use a liturgical format that includes vesicles, the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer.

Actually, the Church used chanting from the very beginning. That was true, in part, because chanting was part of the Jewish synagogue (not Temple) service, which formed the foundation of Christian worship. However, there was another, more practical, reason.

The Church was born in a time before microphones, speakers, and so forth. Chanting is easier to understand over distances than is shouting. That is why yodeling developed in mountain communities. It might surprise you, but we have written records of ministers singing (chanting) their sermons in the early centuries. This was done, not because the pastor had a beautiful voice, but so the sermon could be heard and understood by all attending.

-6-

Speaking of hearing the sermon, that is why pulpits were developed. There was a well-loved pastor we call John Chrysostom (347-407). “Chrysostom” was a nick-name he received because everyone loved his sermons. It means “golden mouthed.” The problem John had was that, while everyone loved his content, they couldn’t hear him. Apparently he had a weak voice. The first pulpit was designed for him with a special curved backing to project his voice towards the congregation. Because John was so well thought of, and because he preached at the famous and important congregation of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (the capital of the empire), and because the innovation worked so well, other congregations began to install pulpits.

Speaking of hearing the sermon, that is why pulpits were developed. There was a well-loved pastor we call John Chrysostom (347-407). “Chrysostom” was a nick-name he received because everyone loved his sermons. It means “golden mouthed.” The problem John had was that, while everyone loved his content, they couldn’t hear him. Apparently he had a weak voice. The first pulpit was designed for him with a special curved backing to project his voice towards the congregation. Because John was so well thought of, and because he preached at the famous and important congregation of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (the capital of the empire), and because the innovation worked so well, other congregations began to install pulpits.

By the way, “pulpit” is from the Latin pulpitum, which was a raised platform. Originally the main architectural differences present in a Christian pulpit were the addition of backing and maybe even a wood canopy (called an abatvoix), which improved the congregation’s ability to hear the sermon.

It is clear, then, that “high church” has nothing to do with the furniture used in a church or even the building itself. A Gothic cathedral can host a “low church” service and an old movie theater can be the location of a “high church” service.

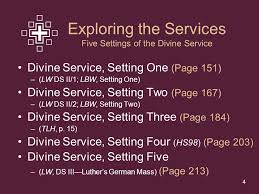

Different Liturgies in Lutheran Service Book

Lutheran Service Book actually has five different settings for Communion. This is more than any of our previous main hymnals in the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. Our first English hymnal (Evangelical Lutheran Hymn-Book) had only one Communion service. Our second English hymnal (The Lutheran Hymnal) also had only one Communion service. Our third English hymnal (Lutheran Worship) had three settings for the Lord’s Supper.

There are variations between the Communion Services found in the Lutheran Service Book, not only in the music, but also in how the services are put together. For example, the creed follows the Gospel lesson in Divine Services three, four and five, but after the sermon in Divine Services one and two. The different locations reflect different theological accents. However, both accents are faithful to God’s Word and the Lutheran Confessions so neither position is “wrong.”

-7-

Each of the Divine Services in our current hymnal is designed as a Communion Service. This accents the “God serves us” theme spoken of above. It is okay to modify them into a service of the Word, which we do on second and fourth Sundays at Our Redeemer, but the general structure remains that of a Communion service. Our hymnal actually has two liturgies that can be used on Sunday mornings that are actual Services of the Word. They are Matins (page 219) and the Service of Prayer and Preaching (page 260). If you look at them you will notice quite a few differences in structure. In this article, though, we will focus only on the Communion services.

Each of the Divine Services in our current hymnal is designed as a Communion Service. This accents the “God serves us” theme spoken of above. It is okay to modify them into a service of the Word, which we do on second and fourth Sundays at Our Redeemer, but the general structure remains that of a Communion service. Our hymnal actually has two liturgies that can be used on Sunday mornings that are actual Services of the Word. They are Matins (page 219) and the Service of Prayer and Preaching (page 260). If you look at them you will notice quite a few differences in structure. In this article, though, we will focus only on the Communion services.

A Three-Part Service

Our Communion services are divided into three parts. The first part is preparatory and focuses on our need for forgiveness. The second part is the service of the Word. The third part is the liturgy of Holy Communion. Originally the preparatory part of the liturgy was a service in itself held prior to the actual service (often Saturday evening). This practice was largely abandoned in American Lutheranism by the early years of the Twentieth Century and today we combine the preparatory portion of the service with both the service of the Word and the service of Holy Communion.

-8-

Announcements

The opening few minutes of our time together on Sunday morning varies from congregation to congregation. Some begin their time together with announcements. Other congregations place their announcements at other times, most often at the end of the service but I’ve also know congregations that did their announcements while the offerings were being collected. Finally, I’ve known of some congregations that make no oral announcements. They depend on the written announcements in the bulletin and newsletter. None of this is “right” or “wrong.” It is all simply according to local tradition. People get accustomed to announcements delivered in a specific way and often have strong feelings about it. I remember a conversation I once had with a layman who told me he would not attend a worship service that didn’t do announcements the way his home congregation did them. Anything else destroyed the Sunday morning worship time. Such an attitude places local traditions and personal feelings above God’s Word, doctrinal unity, and the united experience of the Christian Church. When you visit a congregation while on vacation, don’t let how they do announcements throw you.

Opening Hymn?

![]() The next difference you might experience is whether or not the congregation uses an Opening Hymn, also called a Hymn of Invocation. “Invocation” is Latin and means “call,” as in calling upon God to be present. One might also think of it as God calling us together. The “rubrics” in the hymnal indicate that a congregation “may” sing such a hymn. That means that it is okay if you do this but it is also okay if you don’t. (By the way, “rubric” comes from the Latin word for “red.” The directions in hymnals are traditionally printed in red. Over time “rubric” (red) took on the meaning “instructions in a worship service.” Today the word can be used for any instructions on how to conduct any sort of activity.) While the vast majority of congregations I’ve visited begin with an opening hymn, I’ve noticed a growing trend to omit it. This is especially common, in my experience, with congregations that include more chanting. From a practical point of view, chanting the liturgy takes more time than speaking the liturgy and so, to keep the service to about an hour, the opening hymn is omitted (at least that is what I think). The possible reasons for selecting a hymn were covered above.

The next difference you might experience is whether or not the congregation uses an Opening Hymn, also called a Hymn of Invocation. “Invocation” is Latin and means “call,” as in calling upon God to be present. One might also think of it as God calling us together. The “rubrics” in the hymnal indicate that a congregation “may” sing such a hymn. That means that it is okay if you do this but it is also okay if you don’t. (By the way, “rubric” comes from the Latin word for “red.” The directions in hymnals are traditionally printed in red. Over time “rubric” (red) took on the meaning “instructions in a worship service.” Today the word can be used for any instructions on how to conduct any sort of activity.) While the vast majority of congregations I’ve visited begin with an opening hymn, I’ve noticed a growing trend to omit it. This is especially common, in my experience, with congregations that include more chanting. From a practical point of view, chanting the liturgy takes more time than speaking the liturgy and so, to keep the service to about an hour, the opening hymn is omitted (at least that is what I think). The possible reasons for selecting a hymn were covered above.

-9-

Invocation

The next element is the “Invocation.” In the books that tell pastors how to do the liturgy, this is the first “shall” in the rubrics. That is to say, it is not optional. Saint Paul once wrote, “Whatsoever you do in word or deed, do all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God and the Father by him” (Colossians 3:17). With the words of the invocation we “invoke” (call upon) God so that our service is done “in the name of the Lord Jesus.” The Trinitarian formula sums up all we know about God in a brief scriptural phrase. It also reminds us of our baptism, when we were ushered into the Church and fellowship with the Lord (Matthew 28:19). With these words we acknowledge the presence of God and ask his blessings upon us. The pastor faces the altar, joining the congregation in this request.

Facing the Altar or the Congregation

The location of the pastor, and the direction he is facing, has symbolic meaning. When he is facing the congregation he is speaking for God. When he faces the altar he is speaking for and with the congregation. In church buildings with free-standing altars this distinction isn’t quite as sharp. That is because, when the pastor stands behind the altar, he is both facing the altar and the congregation. Still, it is symbolically helpful to think of him as facing the altar during the prayers, but facing the people when speaking the Words of Institution (more ambiguously called “The Words of Our Lord” in Lutheran Service Book).

Making the Sign of the Cross

Many today continue the ancient custom of making the sign of the cross during the invocation. This practice actually preceded the use of physical crosses in worship services. By this practice the people ask for God’s blessing during the service and remember their baptism, when the cross was first made over them. The invocation and the sign of the cross, then, are reminders that we enter the presence of God only by his grace, his undeserved love and mercy, which is found only in Christ Jesus. This, however, is a “may,” not a “shall” rubric. No judgment should be passed pro or con concerning the practice of others in making of the sign of the cross.

Many today continue the ancient custom of making the sign of the cross during the invocation. This practice actually preceded the use of physical crosses in worship services. By this practice the people ask for God’s blessing during the service and remember their baptism, when the cross was first made over them. The invocation and the sign of the cross, then, are reminders that we enter the presence of God only by his grace, his undeserved love and mercy, which is found only in Christ Jesus. This, however, is a “may,” not a “shall” rubric. No judgment should be passed pro or con concerning the practice of others in making of the sign of the cross.

-10-

Amen

After the invocation, the congregation affirms the pastor’s words with the Hebrew word “Amen.” Martin Luther’s explanation of this word in his Small Catechism is as simple and straight forward as it gets: “Amen, amen means ‘yes, yes, it shall be so.’”

Confession of Sins and Absolution

After the Invocation we move directly into the Confession of Sins and Absolution. The word “confession” means “acknowledgment; avowal; admission.” We actually have two “confessions” in our standard Sunday morning worship service. The first is right after the Invocation and is a confession of our sinfulness. The second time is after the Gospel lesson or sermon and is a confession of our Christian Faith (we typically use one of the three “ecumenical” creeds for this).

After the Invocation we move directly into the Confession of Sins and Absolution. The word “confession” means “acknowledgment; avowal; admission.” We actually have two “confessions” in our standard Sunday morning worship service. The first is right after the Invocation and is a confession of our sinfulness. The second time is after the Gospel lesson or sermon and is a confession of our Christian Faith (we typically use one of the three “ecumenical” creeds for this).

Scripture teaches that we are born sinful and continue to sin even after we become Christians (Psalm 51:5; 1 John 1:8). Scripture also teaches that our Holy God is too pure to look upon sin (Habakkuk 1:13). So, we are urged to confess our sins to God and receive forgiveness (1 John 1:8), which is exactly what we do in this preparatory part of the service. Kneeling is historically a position of humility and submission, reflecting our position before God as repentant sinners. While the Pastor leads us in this confession, he also confesses his own sin and thus kneels facing the altar with the congregation. Not everyone is able to kneel, of course. Standing is also fine.

In settings one and two, our confession of our sinfulness begins with us recognizing our need and our confidence that God will supply our need by using 1 John 1:8-9. In setting three, our confession of our sinfulness begins with three biblical references: Hebrews 10:22; Psalm 124:8; Psalm 32:5. They assure us that, while we are confessing our sins, our Lord and God is favorably disposed towards us. Therefore, we need not fear our sins will come back to haunt us. God bids us come so that he can forgive. (In fact, it is when we do not confess our sins and receive absolution from the Lord that our sins come back to haunt us.) Setting four uses Psalm 124:8, Psalm 130:3-4 and Luke 18:13 to offer us the same assurance. Setting five uses the same biblical references as setting three.

In settings one and two, our confession of our sinfulness begins with us recognizing our need and our confidence that God will supply our need by using 1 John 1:8-9. In setting three, our confession of our sinfulness begins with three biblical references: Hebrews 10:22; Psalm 124:8; Psalm 32:5. They assure us that, while we are confessing our sins, our Lord and God is favorably disposed towards us. Therefore, we need not fear our sins will come back to haunt us. God bids us come so that he can forgive. (In fact, it is when we do not confess our sins and receive absolution from the Lord that our sins come back to haunt us.) Setting four uses Psalm 124:8, Psalm 130:3-4 and Luke 18:13 to offer us the same assurance. Setting five uses the same biblical references as setting three.

-11-

After we confess our sins we move to the Absolution. With the Absolution we receive forgiveness of our sins. That which separates us from God is absolved. Christ granted this awesome power to his Church when he said, “If you forgive the sins of anyone, they are forgiven; if you withhold forgiveness from anyone, it is withheld” (John 20:22-23). The Pastor, now speaking for God and with the words of God, faces the congregation. After the Absolution we are able to stand in the presence of God and so the ongregation rises.

After we confess our sins we move to the Absolution. With the Absolution we receive forgiveness of our sins. That which separates us from God is absolved. Christ granted this awesome power to his Church when he said, “If you forgive the sins of anyone, they are forgiven; if you withhold forgiveness from anyone, it is withheld” (John 20:22-23). The Pastor, now speaking for God and with the words of God, faces the congregation. After the Absolution we are able to stand in the presence of God and so the ongregation rises.

Following the opening scripture lessons, Divine Services one and two offer only one way to confess our sins. Divine Services three, four and five provide two different formats for confession of our sins. Each setting offers two different forms of absolution. In Divine Services three, four and five, the left-hand column is used when the Lord’s Supper is celebrated and the right-hand column is used when we are not celebrating the Lord’s Supper. You can see this distinction in the services found on pages 5 and 15 of The Lutheran Hymnal. The left-hand column is an absolution proper while the right-hand column is a declaration of grace. Because the wording of the left-hand column has the phrase, “I, by virtue of my office, as a called and ordained servant of the Word,” this option would only be used by ordained pastors. The right-hand column is more generally worded and can appropriately be used by any Christian, say, in one’s home.

Over the years many people from a non-Lutheran background have spoken to me about this portion of our service. They have, typically, one of two responses. They might object to it, claiming “only God can forgive sins” (Mark 2:7; Isaiah 43:25). This is, of course, the objection the Jewish leaders raised against Jesus when he forgave sins. It is just as out of place today as in Jesus’ day because of the promise in John 20 quoted above. In our service it is God who is forgiving. He is doing it through his called and ordained minister. The other common response is pure joy. I can’t tell you how many “general” Protestants have told me that they have never before heard, in a worship service, “your sins are forgiven.” They are thrilled to hear, week after week, “you are forgiven.” Perhaps we long-time Lutherans have lost something of that great thrill.

The confession of sins and absolution concludes the preparatory portion of the service.

-12-

Introit/Psalm

The next major section of our worship service is the “Service of the Word.” It begins with either an Introit or a Psalm (sometimes called an Introit Psalm).

The word Introit is Latin and means “entrance” or “beginning.” Having been forgiven our sins we may “enter” the presence of our Holy Lord and “begin” our worship service proper. To symbolize this entering into the presence of God during the Introit or Psalm, the pastor walks towards the Altar and then steps past the Altar Rail.

The word Introit is Latin and means “entrance” or “beginning.” Having been forgiven our sins we may “enter” the presence of our Holy Lord and “begin” our worship service proper. To symbolize this entering into the presence of God during the Introit or Psalm, the pastor walks towards the Altar and then steps past the Altar Rail.

Originally the Introit was the Psalm of the Day, coupled with the Gloria Dei. An antiphon was selected from the Psalm that encapsulated the key thought of the Psalm and the Day. The antiphon is spoken/chanted before the Psalm and after the Gloria Dei. Over time, as the services became longer and longer due to the addition of more and more liturgical elements, the Psalm was shortened to the Introit (selected verses from the appointed Psalm, along with the Gloria Dei and the antiphon). With the liturgical cleansing that happened during the Reformation, many congregations felt they had time for the full Psalm once again.

The word “antiphon” comes from the Greek word antiphonon. The Greek word means “sounding against, responsive sound, singing opposite, alternate chant.” The Latin word, antiphona, has the same meaning.

As the Psalm of the Day or Introit is the first portion of the liturgy that changes from week to week, it is the first “proper.” (Remember, “propers” are the changeable portions of the liturgy and “ordinaries” are the portions of the liturgy that remain constant from week to week.) Therefore, the Introit/Psalm of the Day is the first sounding of the liturgical theme of the day.

-13-

Many, but not all, congregations use the Introit on Communion Sundays and the appointed Psalm of the Day when they are simply having a Service of the Word. Aside from practical concerns (communion services are longer, and Introits are shorter than the Psalm), this also recognizes the historical reality that Introits developed in Communion services while services of the Word always retained the use of Psalms.

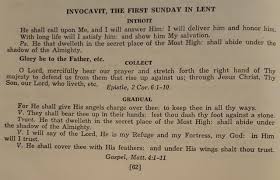

Some may remember from their childhood the traditional Introits. They were keyed to the old one-year lectionary. Those old Latin names for Sundays, like Invocavit, Quasimodogeniti and Jubilate, were (typically) the first word from the Introit in Latin. When most of the Synod went to a three-year lectionary (when Lutheran Worship was introduced), those old Latin names no longer fit. That is because the Introits and Psalms were changed to match with the new three-year lectionary. However, a significant minority of our congregations still use the old one-year lectionary and many of them continue to use the old Latin names.

I might also point out that, with the introduction of the three-year lectionary, many of the new Introits included non-Psalm Scripture lessons or liturgical verses. An Introit that is drawn from the Psalms is called “regular.” An Introit that is drawn from other sources is called “irregular.”

I might also point out that, with the introduction of the three-year lectionary, many of the new Introits included non-Psalm Scripture lessons or liturgical verses. An Introit that is drawn from the Psalms is called “regular.” An Introit that is drawn from other sources is called “irregular.”

The Psalm may also be used between the Old Testament and Epistle lessons, instead of the Gradual, but it serves a different purpose there, and we will discuss that when we get to it.

Introits and Psalms may be chanted or spoken. This may be done by the half verse or by the whole verse. Neither is better than the other.

-14-

Kyrie

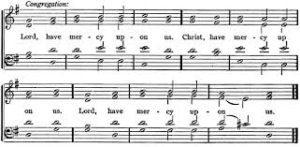

Following the Introit is the “Kyrie.” It is actually a prayer and it is typically set to music, but it doesn’t have to be. This prayer expresses the joy we have as we enter the presence of the Lord. “Kyrie” is the first word in the Latin phrase Kyrie Eleison, which means “Lord have mercy.” This prayer is found in many places in the Bible (Matthew 15:22; Luke 17:13; etc.). The Kyrie is not a prayer confessing our sins and asking for forgiveness (which we did during the preparatory portion of the service), but a cry that God, in his mercy, may hear and help us in our necessities and troubles.

The actual words of the Kyrie have fluctuated a bit over the centuries, but have always included “Lord, have mercy.” By the time of Gregory the Great (540-604), these words were repeated three times, reminding us of the Trinity. The first “Lord, have mercy” was in reference to the Father. The second “Lord, have mercy” was a petition to the Son. The third was a prayer to the Holy Spirit. In time, the second “Lord, have mercy” was changed to “Christ, have mercy.” This is how the Kyrie is in Divine Service, setting four. Divine Service, setting three has the “Lord, Christ, Lord” pattern, but adds the phrase “upon us” after each of the requests for mercy. This is how the Kyrie was in the two main services found in The Lutheran Hymnal. This modification is also quite ancient.

Settings one and two of the Divine Service in our hymnal abandon the triple request, expanding it to a four-part Kyrie. It, therefore, does not seem to have a sharp differentiation between the persons of the Godhead, so we should think of the Trinity with each use of the name “Lord” and not one or the other of the Persons of the Godhead. This form does make it easier to know that the Kyrie is a prayer for God’s aid in our necessities and troubles, and not a prayer asking for forgiveness. This particular form was introduced to us in the hymnal Lutheran Worship. Settings one and two use the same words but employ different tunes. Those words are:

-15-

Because this is not a confession of sins and absolution, the word “salvation” in the second petition should probably be thought of as saving us from some present problem. For example, if we were being persecuted, we could pray for salvation from the Lord, that is, that he might rescue us. In this sense, we are often in need of salvation.

Using the phrase “Lord, have mercy” as a response to petitions in a prayer was a common practice in the Eastern Church during Gregory’s time and is probably where the idea for using it in the Western liturgy came from. They often, in prayers like the Litany, interspersed the supplications with “Lord, have mercy.” This can be seen, in a modified form, in the Litany on page 288 in Lutheran Service Book.

To sum this up in succinct style, the Kyrie is a prayer for God’s mercy in our everyday lives.

-16-

Hymn of Praise

Following the “Kyrie” is the “Hymn of Praise.” While various hymns can be used, historically the Church has used the Gloria in Excelsis Deo to praise our Triune God at this point in the service. Gloria in Excelsis Deo is Latin and means “Glory to God in the highest,” the very words used by the angels to proclaim the birth of the Savior to shepherds (Luke 2:14). This Hymn of Praise proclaims the glory of God and expressing the joy of the believers in God’s merciful goodness in sending his Son to be the Savior of the world.

Because the words of this hymn are taken from the angels when Christ was born of the Virgin, it accents the incarnation, the presence of God on this earth to bring us forgiveness of sins and salvation. Heaven had come down to earth! Ever since this miraculous event, the Church has continued to rejoice in this divine gift that brings our salvation.

Because the words of this hymn are taken from the angels when Christ was born of the Virgin, it accents the incarnation, the presence of God on this earth to bring us forgiveness of sins and salvation. Heaven had come down to earth! Ever since this miraculous event, the Church has continued to rejoice in this divine gift that brings our salvation.

After the quote from the angels, the “Gloria” continues with a hymn of praise to the Triune God. The faithful sing: “We praise you, we bless you, we worship you, we glorify you, we give you thanks for your great glory.” Our focus is on the incarnate Son of God, the only-begotten Son, the Lamb of God, and only Son of the Father. And if that isn’t enough to name this One who is the object of our worship and praise, twice we sing, “you take away the sin of the world.” There it is, the heart and substance of the Christian faith.

It is no surprise, with all this accent on the incarnation, that the “Gloria” became the standard hymn of praise when the congregation celebrates the Lord’s Supper. After all, in the Supper, Jesus still comes to us with his body and blood to grant us forgiveness and salvation.

Like the “Kyrie,” the “Gloria” came into the Western tradition’s Communion liturgy from the Eastern Church. When introduced into the West, it was first used as a song of thanksgiving. The earliest record of its inclusion in a Communion service is from around 530 ad. Tradition has it that it was first used by the pope on Christmas Eve.

-17-

Many of our congregations, however, do not celebrate the Lord’s Supper every Sunday. Such congregations have the option of using one of the liturgies specifically designed as a service of the word (Matins, LSB 219; Service of Prayer and Preaching, LSB 260) or using a truncated form of the standard Morning Service (Morning Service is what this service was called in The Lutheran Hymnal).

In The Lutheran Hymnal both the truncated and full forms of the morning service used the “Gloria” (pages 5 and 15) but, in 1970, a new hymn of praise was introduced into Lutheran churches titled “This is the Feast.” In the LCMS, “This is the Feast” (LSB 155, 171) was introduced in 1982 with Lutheran Worship (161 first setting, 182 second setting). It also appeared in Lutheran Book of Worship (LBW 60 setting one, 81 setting two, and 102 setting three). Three different tunes are used in these books.

“This is the Feast” draws directly from the description of heaven in the Revelation to St. John. In it we join our voices to that heavenly throng as we sing with them praise to the resurrected and ascended Lord (Rev. 5: 9-13; 19:4-9). We rejoice with all who attend the “marriage supper of the Lamb” (19:9). The “feast” sung of, then, is not the Lord’s Supper, but the great feast all saints share in glory! In this hymn of praise, we look forward to the final consummation of time and the ushering in of the new heavens and new earth when Jesus returns to claim his own.

“This is the Feast” is, theologically, better suited for services where the Lord’s Supper is not celebrated. The reality is that many people truly like this new hymn, even in churches that celebrate Communion every Sunday. Therefore they use “This is the Feast” as well as the “Gloria.” They are not wrong when they do this. Yes, the words are a little out of sync with the design of the service, but the words are still solid. It might be like singing “The Lord God is my strength and my song,” another new hymn of praise designed for a service of the word and used in the new “Service of Prayer and Preaching” (LSB 260). It is solid, biblical, and theologically sound; it just doesn’t overtly direct us towards Communion.

-18-

When “This is the Feast” is used during a communion service, you might want to think of the Lord’s Supper as a foretaste of the heavenly banquet (though we will not have the Lord’s Supper in glory because we will no longer need forgiveness of our sins (Revelation 7:14), nor will there be a need for the Supper to strengthen our presence with Christ as we will be seeing him “face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12), nor will it be needed to strengthen our connection with the redeemed in Glory as we will be part of that heavenly throng (Revelation 19:6)). Still, it is a way to think of “This is the Feast” in reference to Communion.

Salutation and Collect of the Day

The Salutation is a biblical way that the children of God greeted each other in the New Testament and reflects the special relationship we have in the Lord. Various forms of this greeting can be found in places like 2 Timothy 4:22, Galatians 6:18, and Philemon 25. The variation between “and with thy/your spirit” and “and also with you” is simply in style, not content.

The Collect of the Day is also called the “Prayer of the Day.” A “collect” is a short prayer that reflects the theme of the day. They have been called “an arrow shot to heaven.” A full Collect follows a specific pattern. First, God is addressed in terms of what the petition will be about. If it is a prayer for healing, the Collect might begin by addressing Jesus as the Great Physician. If it is a prayer for aid, the prayer might begin by addressing God as merciful, or perhaps almighty. The next part of the prayer expresses something God has done that reflects the subject of the prayer. So, for example, a prayer for healing might recall any of the times God has healed in the past. A prayer for safety while traveling might reflect how God guided Abraham in his travels, or the Holy Family when they fled to Egypt. The fourth part of a full Collect is the actual petition. The fifth and final part is the conclusion. In a full Collect the conclusion is Trinitarian. So, one might pray, “through Jesus Christ, Your Son, our Lord, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.”

-19-

There are ample examples of Collects that do not reflect this full pattern and you can find some in our hymnal in the collection of prayers found on pages 305 through 318, though most follow the full pattern. On those pages you will find prayers for all kinds of things, both in relation to our Church life and our lives beyond.

There are specific collects appointed for each Sunday, as well as for Feasts and Festivals of the Church year. They generally reflect a main theme from the appointed readings. The Collect of the Day is a “Proper.”

Appointed Scripture Lessons

In a typical Lutheran worship service, so far, there has been a gradual approach to the altar of our God. We have spoken of our sin, our need for forgiveness, praise for that forgiveness, and our desire for continued aid from our God. We now pause in reverence to hear God speak to us from his word.

In a typical Lutheran worship service, so far, there has been a gradual approach to the altar of our God. We have spoken of our sin, our need for forgiveness, praise for that forgiveness, and our desire for continued aid from our God. We now pause in reverence to hear God speak to us from his word.

Reading from the Bible is a practice that the Christian Church took right over from the Jewish Synagog service. We find our Lord participating in this practice in Luke 4:16-21 where he read from the book of Isaiah. Justin Martyr, a second century Church Father, wrote about the Church’s typical Sunday morning worship service:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things.

You can see that the New Testament writings were included in the readings as having equal value with the Old Testament writings. You can also see that a sermon was delivered by the leader of the congregation.

When we consider just a few quotes from the Bible concerning the Word of God, it is not surprising that the Scriptures held such a vital place in Christian worship in the past, as it does in a typical liturgical service today.

-20-

This God—his way is perfect;

the word of the Lord proves true;

he is a shield for all those who take refuge in him. (2 Samuel 22:31)

The grass withers, the flower fades,

but the word of our God will stand forever. (Isaiah 40:8)

For the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart. (Hebrews 4:12)

For the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart. (Hebrews 4:12)

… and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God … (Ephesians 6:17)

In recent years a special message for children has been added in many Lutheran churches. Because there is no official spot to give this message, different churches that engage in the practice do so in various places. Because this practice is a special message from the word of God to children, I feel the most logical place to include a Children’s message is when the Scriptures are being read. I prefer just before our Old Testament lesson. In general, this practice reflects the words of Jesus in Mark 10:13-16: “Let the children come to me; do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of God.”

The Gradual or Psalm of the Day is read or chanted between the Old Testament and Epistle lesson. If the Psalm is used here it is often called the Gradual Psalm. These “Propers” (the Gradual or Psalm) reflect the liturgical theme of the day. The Gradual, or Gradual Psalm, represents stepping up from the Old Testament revelation to the greater clarity of the New Testament.

-21-

After the Epistle lesson we come to the Gospel lesson. Various ways have been used to draw attention to the Gospel lesson over the years, including singing it. In our hymnal we rise for this reading from the story of our Savior out of respect for him and surround it with ascriptions of praise. The pastor reads the Gospel lesson while, in many congregations, an assistant reads the other lessons. This is another way of showing the elevated place of the Gospel. Pastors often even move to another place to read the lesson so that our eyes may follow the Gospel. In many congregations the Pastor moves to the center of the congregation, symbolizing the Gospel of God coming to the people in the person of Jesus Christ. Other elements can be incorporated, all to accent what a blessing it is that Jesus has come to us and still comes to us through the Word.

Creed

In settings three, four and five, the reading of the scripture lessons is followed by our confession of faith using one of the historic Ecumenical Creeds (Apostles’, Nicene and Athanasian). In settings one and two the confession of faith follows the sermon.

So much could be written about each of the creeds that many volumes could be filled with commentary on them. For our purpose, what we need to remember is that each of the creeds is an epitome of what the Scriptures teach. It is on these truths that the Church has stood from the first century (in fact, the Apostles’ Creed is so named because it expresses the faith the Apostles taught).

So much could be written about each of the creeds that many volumes could be filled with commentary on them. For our purpose, what we need to remember is that each of the creeds is an epitome of what the Scriptures teach. It is on these truths that the Church has stood from the first century (in fact, the Apostles’ Creed is so named because it expresses the faith the Apostles taught).

There are many today that deny the historical fact that the creeds reach back to the Apostles. While the Apostles did not use the creeds as we have them, they certainly did teach the truths contained in them. This is the united witness of all Early Church Fathers.

Anyway, as the creeds are epitomes of what the Word of God teaches, we confess them during the section of the service that we call the “Service of the Word.” However, as I said, exactly when we confess the creeds varies from setting to setting. As it is always in the Service of the Word, the following observation from Luther Reed is appropriate:

-22-

The Creed … is the church’s reply to God’s Word, the public acceptance and confession in summary form of the faith of the whole church. Every use of it is in a sense a renewal of our baptismal covenant. Its brief but comprehensive statements encompass “the whole dispensation of God.” It outlines and preserves, in balanced proportion, Christianity’s fundamental beliefs; it witnesses to the perpetual unity, and universality of the Christian faith; it binds Christians to one another and to the faithful of all centuries. (Reed, Luther The Lutheran Liturgy 302)

Whether we confess the Creed after the Gospel lesson or after the sermon, it enables the congregation to view and review the whole horizon of the Church’s belief. There are, though, slightly different accents based on the placement. When following the Scripture lessons it is thought of as a concise statement of what the Word of God teaches. It is God’s Word to us. When following the sermon the accent is on us responding to God’s Word with the faith proclaimed in the creed. It is a corporate expression of praise and thanks, reciting what God has done for our salvation.

Sermon

The sermon follows the scripture lessons in the first, second, and fourth settings of the morning service and after the creed in the third and fifth settings. In a typical Lutheran service the minister draws inspiration for his sermon from one of the appointed lessons of the day (Old Testament, Epistle, Gospel or Psalm). It is an application of God’s word to our current setting and, as such, is God’s word to us. This is no place for political or social agendas. Not that there is anything un-Christian about having political or social goals, it is just that this is not the time or place for them. Here we hear God’s timeless word and have our eyes fixed on his goals. We are shaped by his word. Yes, the Holy Spirit can use the words to shape our political or social goals, but it is even more likely that the Holy Spirit will use the words to shape our day-to-day lives. It is especially more likely that the Holy Spirit will use the words of the sermon to shape our relationship with God himself and conform us into the image of Jesus. After all, political and social agendas will all be gone at the Second Coming, but the image of Christ we are being transformed into will endure for all eternity.

The sermon follows the scripture lessons in the first, second, and fourth settings of the morning service and after the creed in the third and fifth settings. In a typical Lutheran service the minister draws inspiration for his sermon from one of the appointed lessons of the day (Old Testament, Epistle, Gospel or Psalm). It is an application of God’s word to our current setting and, as such, is God’s word to us. This is no place for political or social agendas. Not that there is anything un-Christian about having political or social goals, it is just that this is not the time or place for them. Here we hear God’s timeless word and have our eyes fixed on his goals. We are shaped by his word. Yes, the Holy Spirit can use the words to shape our political or social goals, but it is even more likely that the Holy Spirit will use the words to shape our day-to-day lives. It is especially more likely that the Holy Spirit will use the words of the sermon to shape our relationship with God himself and conform us into the image of Jesus. After all, political and social agendas will all be gone at the Second Coming, but the image of Christ we are being transformed into will endure for all eternity.

-23-

The sermon is actually the first high point in a Communion service (communion being the second). This is kind of obscured in settings one and two, where the Creed comes after the sermon. Still, you know the reasoning from the above section. In a service of the Word, it is the sole high point.

Offering

After having been blessed by God’s forgiveness and his word, we have a natural desire to respond, to express our gratitude. We do this with our gifts. In the Early Church, along with money to provide for the poor and other expenses, the elements for the Lord’s Supper were presented by the congregation members during this time.

God, of course, has no need for our gifts of money or other items (Psalm 50:10-12). However, we need to respond, to express our faith in such a manner. In our culture, worth is often expressed in monetary fashion. One can often tell what a person’s priorities are simply by looking at where they spend their money. God calls on us to place him at the top of our list of priorities. He comes before health, family, vacation, a new car, or anything else. Many have said that 10% of our income is a good amount to give. This is based on the Old Testament (Leviticus 27:30; Numbers 18:26; Deuteronomy 14:24; 2 Chronicles 31:5). However, these laws were for the Old Testament nation of Israel and are not part of the Moral Law. Nowhere in the New Testament is tithing recommended. This is one reason Lutherans typically speak of “offerings” and not “tithes.” The New Testament tells us to give as God has prospered us. If you feel the Lord has been especially good to you, then you give more. However, your giving should always be within your means (1 Corinthians 16:2). Every Christian should diligently pray and seek God’s wisdom in the matter of how much to give (James 1:5). Above all, offerings should be given with pure motives and an attitude of worship to God and service to the others. “Each man should give what he has decided in his heart to give, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver” (2 Corinthians 9:7). From the very beginning the Church has offered support for both those inside and those outside the family of Christ (Galatians 6:10). Offerings should never be given in an effort to manipulate God! Offerings are an expression of our faith and love towards God and a desire to see his Kingdom grow. Our offerings are a response to God’s mercy.

-24-

Prayer of the Church

We are told that without faith we cannot approach God (Hebrews 11:6). At this point in the service, we have confessed our sin and been absolved, we have heard God’s word and been instructed in it, we have confessed our faith using one of the Ecumenical Creeds and we have shown our faith in our offerings. We are now prepared to approach God with our prayers.

We are told that without faith we cannot approach God (Hebrews 11:6). At this point in the service, we have confessed our sin and been absolved, we have heard God’s word and been instructed in it, we have confessed our faith using one of the Ecumenical Creeds and we have shown our faith in our offerings. We are now prepared to approach God with our prayers.

In fact, prayer is one of the marks of the congregation gathered in worship (Acts 2:42; 3:1). The congregation, established and gathered by God according to his purpose, agrees together on earth that it may be done for them by the Father in heaven (Matthew 18:20-21), as prayer, supplications, and thanksgiving are offered for all in authority, all manner of human needs (1 Timothy 2:1-4), and especially for the Kingdom of God and its expansion (Matthew 6:10). The “Prayers of the Church” are part of our offering to God and is a response to the mercy of God found in Christ Jesus our Lord. The Church here is the Universal Church and not just the local congregation. The prayers, therefore, always include global concerns as well as local concerns (Galatians 6:10).

Back in the days of The Lutheran Hymnal what we currently call “The Prayer of the Church” was called “The General Prayer.” This prayer was printed out in the hymnal. There was a different prayer for each of the main services (the services that began on pages 5 and 15). These two wonderful, but long, prayers are not in the Lutheran Service Book, which is a shame, in my opinion. They are a great option. Of course, we are free to use them if we desire.

Many churches use the prayer offered by the Synod for each Sunday of the year (https://www.lcms.org/worship/three-year-series-prayers). These prayers accent thoughts drawn from the Scripture lessons for the day as well as relate to items happening around the nation and the world. They also provide a space for local

-25-

concerns, especially for those who are ill. Each petition is followed by a response from the congregation. It is, therefore, something of a Litany format or a petition format. Those who plan the service are free to omit or modify the petitions, as well include additional petitions. In other congregations, the pastors pen their own prayers or use historic collects such as those that can be found on pages 305-308 of Lutheran Service Book. A third option used in some of our sister congregations is for the pastor to lead the prayer ex corde. “Ex corde” is Latin and means “out of the heart.” In other words, it is an extemporaneous prayer. All these practices are perfectly acceptable. None is intrinsically superior to the other. The Church prays; that is the big thing.

The Prayer of the Church is the last part of the Service of the Word. Therefore, it is thought of as us speaking God’s Word back to him. A “good” Prayer of the Church is saturated with ideas and thoughts from the Bible.

When we do not celebrate the Lord’s Supper, the service quickly ends. We pray the Lord’s Prayer, a short collect, have a final benediction and close with a hymn. When we do celebrate the Lord’s Supper, the Prayer of the Church leads us into the third part of our service, the Service of the Sacrament, where Christ gives to us the gifts of his body and blood in, with, and under, the bread and wine (Matthew 26:26-28).

While the Prayer of the Church is part of the Service of the Word, it is not because our prayers are the Word of God, but because they reflect the Word of God. They express how we are shaped by the Word of God. This is an important distinction because the Word of God is a Means of Grace, but our prayers are not. Our prayers are a response to God’s grace.

Service of the Sacrament

![]() The Church has been established by Christ to administer his Word and Sacraments; these are the true marks of the Church. She fails in her duties to her Lord if she fails in either of these callings. So far we have considered how our worship services remain faithful in the first half of our worship, to the “Word” half of our charge from the Lord. Having heard the Word we turn to our second great privilege of administering the Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood.

The Church has been established by Christ to administer his Word and Sacraments; these are the true marks of the Church. She fails in her duties to her Lord if she fails in either of these callings. So far we have considered how our worship services remain faithful in the first half of our worship, to the “Word” half of our charge from the Lord. Having heard the Word we turn to our second great privilege of administering the Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood.

The service of the Word is for all. Communion is for those who are mature in their Christian faith (1 Corinthians 11:28). They have been baptized and have received the instruction of the Church. They know they receive through this sacrament the real physical body and blood of Jesus for the forgiveness of their sins. They know that Communion is more than a symbol or simple fellowship meal, for we commune with the Lord and all the saints in Glory. It is the second high point in the Service of the Sacrament, where Christ comes to us and serves us himself for our forgiveness.

-26-

Preface

We begin the Service of the Sacrament with the Preface. It is a liturgical introduction to the liturgy of Communion which leads into the heart of the service. The “Common” Preface is divided into two parts. The first part is a salutation, which is a biblical greeting (P: The Lord be with you. C: And with thy spirit.). It then proceeds to a strong call to the believers to elevate their hearts and souls above all earthly things (Lamentation 3:41; Psalm 86:4). These two elements together are the “Common Preface.”

The Common Preface is the oldest and least-changed part of the service, being witnessed to as early as 220 ad (Hippolytus). These words remain the same every time we celebrate the Lord’s Supper. Its strong words of praise remind us of our Lord’s own actions when he instituted the Supper (Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:24).

In settings one and two, an element of thanksgiving is added. It is taken from Psalm 1:36 and is in keeping with the spirit of the older words. Here we encourage each other to have thankful hearts. As we approach the Table of our Lord, our hearts do indeed overflow with thanksgiving.

Following the Common Preface we have the “Proper Preface.” The Proper Preface actually changes and is a commemoration of our Lord based on the season of the Church Year. It is, therefore, a “Proper,” while the Common Preface is an “Ordinary.” The Proper Preface, however, always begins with, “It is truly meet (or “good”) right, and salutary that we should at all times and in all places give thanks to You, holy Lord, almighty Father, everlasting God, through Jesus Christ, our Lord,” and ends with “Therefore with angels and archangels and with all the company of heaven we laud and magnify Your glorious name, evermore praising You and saying.” It is followed by the Sanctus. We make one slight modification at Our Redeemer. As we actually sing the Sanctus, the final word we use is “singing,” not “saying.”

-27-

The various prefaces for the different seasons were in our previous hymnals. However, they have been omitted from Lutheran Service Book. This was probably done for space reasons. The various prefaces can be found in other companion volumes, like the Altar Book. If you have a copy of Lutheran Worship, you can find the Proper Prefaces on pages 146-148. If you have a copy of The Lutheran Hymnal, you can find the Proper Prefaces on page 25.

Over the years of my life, the number of Proper Prefaces commonly used in the LC-MS has increased. In The Lutheran Hymnal, there were 9. In Lutheran Worship, there were 11. In our current hymnal (Lutheran Service Book), there are 20. This reflects the trend towards being more “liturgical” in our denomination. So, for example, there was no designated Proper Preface for Holy Week in The Lutheran Hymnal, but in Lutheran Worship there is. Neither The Lutheran Hymnal nor Lutheran Worship has a Preface for use in weekday service, but Lutheran Service Book does.

I expect this trend of growing options to continue for the rest of my life in both our denomination and others. However, somewhere down the road, there will be a reaction against it, and the trend will become growing simplicity. This will happen when enough people in the pew feel the heart and soul of a Word and Sacrament service is being obscured.

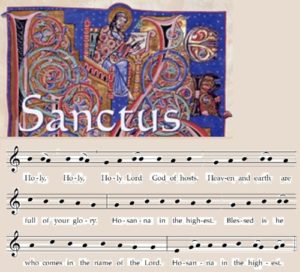

Sanctus

The Sanctus follows the Preface. “Sanctus” is a Latin word that means “holy.” It is actually the climax and conclusion of the Preface. In it the congregation dramatically joins in the song of the angels. It is an act of adoration and thanksgiving in the spirit of holy awe.

We actually have three different translations of this ancient song in our worship services. The first is used in Divine services one and two. A second is used in Divine service three, a third in Divine service four. Divine service five suggests several hymns.

-28-

The first line is in praise of the Father. Our first translation is, “Holy, holy, holy Lord God of Pow’r and might: Heaven and earth are full of Your glory.” Our second translation is, “Holy, holy, holy Lord God of Sabaoth, heav’n and earth are full of Thy glory.” “Sabaoth” is a Hebrew word and means “almighty.” Our third translation has, “Holy, holy, holy Lord God of Sabaoth adored. Heav’n and earth with full acclaim shout the glory of Your name.”

Clearly, the first line is in praise of our almighty Father, and we join with the angels in that praise (Isaiah 6:3).

The second line is in praise of the Son. The first translation has “Hosanna. Hosanna. Hosanna in the highest, Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.” The second translation is like the first, only it repeats some of the lines. The third translation is, “Sing hosanna in the highest, sing hosanna to the Lord; Truly blest is He who comes in the name of the Lord!” The word “Hosanna” is Hebrew and means “save now.”

The word’s “Holy, holy, holy,” echo the words of the seraphim in Isaiah 6:3 as they praise the “Lord sitting upon the throne, high and lifted up,” “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” This is but a very concise restatement of Genesis one and two. One is also reminded of Psalm 19:1-6. We also remember the words of the “four living creatures” in Revelation 4:8, who unceasingly proclaim “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come!”

The second line clearly reflects the words of the Palm Sunday crown who shouted, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” (Matthew 21:9). We also think of Matthew 23:39, Mark 11:9, Luke 13:35, and so forth. The source of these words of praise is Psalm 118:26, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! We bless you from the house of the Lord.” So, we express our desire for our Lord Jesus to come and save.

The second line clearly reflects the words of the Palm Sunday crown who shouted, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” (Matthew 21:9). We also think of Matthew 23:39, Mark 11:9, Luke 13:35, and so forth. The source of these words of praise is Psalm 118:26, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! We bless you from the house of the Lord.” So, we express our desire for our Lord Jesus to come and save.

That is, after all, what the Lord’s Supper is all about. Jesus comes to us under the bread and wine with his saving body and blood. The fact that this song has been associated all over Christendom with Communion since at least as early as the Third Century, and possibly during the days of the Apostle’s, as Augustine and other Church Fathers believed, is perfect. The Sanctus builds our excitement as we anticipate our saving Lord coming to us in his Sacrament.

-29-

The Communion Prayers

During the roughly one thousand years we call the Middle Ages, the liturgy of the church greatly expanded. By the time of Martin Luther, it included long prayers that reflected corrupted theology, and that included the prayers associated with Communion. Among other things, in the prayers the priest, it was held, transformed the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ and then re-sacrificed Jesus in an “unbloody” sacrifice. The Words of Institution were part of the prayer and the transformation was said to occur as the priest said the words “This is my Body” and “This is my Blood.”

[A small aside: Many believe that the term “Hocus Pocus” comes from the Latin “Hoc est corpus meum” (This is my Body). The priest would mutter this phrase, so the average layman couldn’t hear it clearly, but they believed that the phrase “magically” changed the bread.]

The long prayer that included so much bad theology (like invoking the saints) today is called, by Lutherans, either “the Prayer of Thanksgiving” or “the Eucharistic Prayer.” Luther was a great “liturgist” and revisited the entire Sunday morning worship service. He returned it to a simpler form, like what was used in the late classical and early middle ages. One of the changes he made was to excise the Words of Institution from the lengthy prayer and simply omit the rest of the Eucharist Prayer altogether (although the prayer was already in place before the year 500). This omission was common in American Lutheranism until halfway through the 20th century.

In 1969 the Synod published Worship Supplement, which was used to test various materials with people before the publication of a new hymnal. Worship Supplement reintroduced the Prayer of Thanksgiving, purged of false doctrine, which was then retained in Lutheran Worship. It remains in settings one, two and four of the Divine Service in Lutheran Service Book. It is not in setting three, as that service seeks to reflect The Lutheran Hymnal (both page 5 and page 15), and that hymnal did not have a Eucharist Prayer.

-30-

This is not a return to the theology of the High Middle Ages. Our prayers not only reflect biblical teaching, but more precisely are focused on thanking God for the salvation merited for us by Jesus and the gift of the Lord’s Supper. By including this prayer we reflect the night when Jesus established this Sacrament. Luke 22:17-20 records Jesus “giving thanks” with both the wine and the bread as he instituted the Lord’s Supper. He wasn’t thanking the disciples for joining him. This was a prayer of thanksgiving. (By the way, the word “Eucharist” is a transliteration of the Greek word used in Luke and translated “thanks.”)

Following the Eucharist Prayer, in settings one and two, we are given two options, one in the left-hand column and one in the right-hand column. In the right-hand option, the Prayer of Thanksgiving is followed by the Lord’s Prayer. This perfect prayer sums up everything that we are to pray about. In Matthew’s account, found in chapter 6, Jesus introduces the Lord’s Prayer with the words, “Pray then like this” (Matthew 6:9). Luke (11:2) records Jesus as prefacing the Lord’s Prayer with the words, “When you pray, say.” With these words we again confess the unity of the Church of Christ as we petition the Lord in the same fashion the saints have done since the time of Jesus. This is the format followed in settings three through five.

Following the Eucharist Prayer, in settings one and two, we are given two options, one in the left-hand column and one in the right-hand column. In the right-hand option, the Prayer of Thanksgiving is followed by the Lord’s Prayer. This perfect prayer sums up everything that we are to pray about. In Matthew’s account, found in chapter 6, Jesus introduces the Lord’s Prayer with the words, “Pray then like this” (Matthew 6:9). Luke (11:2) records Jesus as prefacing the Lord’s Prayer with the words, “When you pray, say.” With these words we again confess the unity of the Church of Christ as we petition the Lord in the same fashion the saints have done since the time of Jesus. This is the format followed in settings three through five.

In the left-hand column of settings one and two the Words of Institution (called the “Words of our Lord” in the Lutheran Service Book) follow the Eucharistic Prayer. This is followed by a brief quote of 1 Corinthians 11:26 and Revelation 22:20. Then there is a short prayer (called a “collect”) followed by the Lord’s Prayer. These modifications are thoroughly biblical. I especially like the words in the prayer, “You lead us to remember and confess Your holy cross and passion, Your blessed death, Your rest in the tomb, Your resurrection from the dead, Your ascension into heaven, and Your coming for the final judgment.” These words remind us of the larger picture.

The Words of Our Lord/Words of Institution

We now come to the point of the service where the pastor recites the “Words of Institution,” also called the “Verba” (Latin for “words”). In our current hymnal these words are simply called “The Words of our Lord.”

-31-

While the phrase, “The Words of our Lord,” reflect the Latin “Verba,” I personally prefer the phrase, “The Words of Institution.” I prefer it because Jesus spoke many words during his earthly ministry, but he instituted the Lord’s Supper only once. To the non-Christian, it seems to me like “The Words of our Lord” is confusing. Nonetheless, the current terminology accents that Jesus established Communion, not his followers. It is the Lord who invites us to the Table, not the denomination, congregation or the pastor. It is the Lord who serves us at the Table, not the denomination, congregation or the pastor. It is the Lord who is insulted when we distain the Sacrament, not the denomination, congregation or the pastor. And it is the Lord’s gift we tinker with if we change the Meal, not the Church’s gift or the denomination’s, congregation’s, or the pastor’s.

The words we use are taken from the four accounts of the establishment of the Lord’s Supper, woven together into one smooth lesson (Matthew 26; Mark 14; Luke 22; 1 Corinthians 11). This is more than setting the historical stage for Communion, or a citation of authority for administering the Lord’s Supper. It is our Lord himself speaking to us in his own words and establishing the Meal, the same Meal he shared with his followers on the night he was betrayed. He again promises us that in/with/and under the bread and wine we receive his body and blood, the very body and blood that was broken and shed for us on the cross. At this moment we are joining the Apostles during the first Lord’s Supper, and with all the saints who have shared that meal ever since. The consecration is the consecration Christ performed that night, carried forward by a miracle, so that Christ offers his very body and blood to the communicants.