Thursday after Pentecost

The Lord be with you

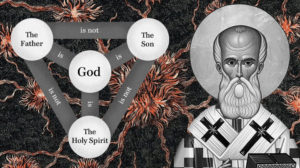

The first Sunday after Pentecost is always Trinity Sunday in the LC-MS. This year that is the coming Sunday, May 22. On Trinity Sunday we use the Athanasian Creed. That is the really long creed no one has memorized. In this post, I am providing some background for the creed.

Like the Apostles’ Creed, no one is really sure who wrote the Athanasian Creed. There is even debate as to when and where it was composed. Some hold to the second half of the fourth century, others to the fifth century, and still others to the sixth century. A very few hold to the ninth century, though that is ridiculous as we have copies of the creed that predate that century. Some believe it was written in or around Alexandria, while others believe it was written in southern Gaul.

Like the Apostles’ Creed, no one is really sure who wrote the Athanasian Creed. There is even debate as to when and where it was composed. Some hold to the second half of the fourth century, others to the fifth century, and still others to the sixth century. A very few hold to the ninth century, though that is ridiculous as we have copies of the creed that predate that century. Some believe it was written in or around Alexandria, while others believe it was written in southern Gaul.

This creed is named after St. Athanasius of Alexandria, a staunch defender of the Christian faith in the fourth century and does faithfully express his faith (and the universal faith of the Church). A medieval account credited Athanasius as the author of the Creed. According to this account, Athanasius composed it during his exile in Rome, and presented it to Pope Julius I as a witness to his orthodoxy. The Pope, by virtue of the creed, recognizes Athanasius as orthodox. The lateness of this story, along with other issues, makes it difficult to believe.

Just about every “big gun” from the church’s history from the late fourth through the ninth centuries has been put forth as the composer of the Athanasian Creed, but all suggestions have a fatal flaw. If some major Church luminary was the author, then surely his name would have immediately been attached to the creed. Think of it this way. We all know who wrote the Gettysburg Address. We know the date and occasion when it was first delivered. That is because Lincoln was president. But what if it had been first written by some civics instructor of a small town and used in a school play. The local newspaper reporter was impressed and put it in the paper, but does not know who actually wrote the words and so writes, “In the play, Lincoln says, ‘Fourscore and seven years ago …’ and inserts the speech.” Then other papers gradually pick up the speech until it spreads around the country. People begin to wonder who wrote it. Recognizing the sentiments of Lincoln, the story begins to circulate that Lincoln was indeed the author. The real author is lost. We know who wrote the Gettysburg Address, because Lincoln was a big gun. We do not know who wrote the Athanasian Creed and so he is probably not a prominent figure in Church history.

The fact that it is being referred to by prominent Christian writers by the middle of the fifth century in southern Gaul is more than enough to reason to assume it was composed sometime in the latter half of the fourth or early part of the fifth century. It was probably written by an obscure bishop for the congregations under his charge for use in their worship services. Though this bishop never made a name for himself, the creed he wrote is powerful testimony to the truth that there is no unimportant service (or servants) in Christ’s Kingdom.

Like the Apostles’ Creed, the Athanasian Creed does not receive “official” recognition until the Reformation. It was indorsed by the Lutherans in the Augsburg Confession (1530) and included in the Book of Concord (1580). The Roman Catholic Church endorsed it at the Council of Trent (1545-1563). It was also indorsed by most Protestant branches that sprung up during the Reformation period (Church of England, Reformed confessions, etc.).

The Latin name for the Athanasian Creed is “Quicumque vult,” which are the first two words of the creed in Latin. They translate “Whosoever wishes”. Though its contents appear to focus on teaching to contemporary readers, its opening actually sets out the essential principle that the Christian faith does not consist in the first place in assent to propositions, but “that we worship One God in Trinity, and the Trinity in Unity;” all else flows from that orientation. The two key elements of true worship in the creed is worship of the Triune God and of Jesus as both fully God and fully man. There are other elements included in the creed, but these two points are clearly the main focus. One key lesson we learn from this, then, is that what we do in worship is VERY important. This is one of my personal concerns with the new ELCA hymnal. It has an option for Sunday morning worship that makes no reference to the Trinity or the true nature of Jesus. It has only generic terms for God.

Some are startled, even troubled, by the “damnatory,” or “minatory clauses,” in this creed (the penalties which follow the rejection of what is proposed for our belief). In reality, they are but the creedal equivalent of Our Lord’s words: “Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil” (John 3:18-19). Clearly these words of Jesus, and the creed, apply only to the culpable and willful rejection of Christ’s words and teachings. In other words, it is rejection of the truth once learned, not ignorance of the truth, that this creed (and Jesus) say are condemned.

This creed, as said above, has always been intended for use in worship. The congregation would either sing or recite it. During the Middle Ages it was used quite often. In some places, every week. In our age, with theology by sound bite, this rich creed is the most overlooked of the three ecumenical creeds. In some churches, it is never used. We only use it once a year, on Trinity Sunday. If we were wise, we would use it far more.

Blessings in Christ,

Pastor